A meteorite fell on the outskirts of a small town. This event stirs the imagination of the locals. This is the first Contact, but… the Martians didn’t come in peace. It took them a long time to closely study the earth to begin their invasion. In just a couple of days, all the cities were destroyed, the armies of the entire world defeated.

It seems that the doom of mankind is inevitable. There is no salvation! And Dr. Clyton Forrester tries to keep his beloved Sylvia from the nightmare going on around her. Will mankind be wiped off the face of the earth?

4k movies reviews

A good book is an important part of a successful film, a source of inspiration for a variety of themes and ideas. From a good book you can find a theme for every time and make it the foundational theme of a new film.

Herbert Wells wrote a tremendous cautionary novel in the late 19th century, covering a gigantic thematic material with it. There were the mores of late 19th century Britain, and exorbitant human hubris, self-love and narcissism, selfishness, the bravado of the ‘crown of nature’, a warning to future generations not to become arrogant, that man may not be the crown of creation, but only a pawn, even more – a mistake of nature, which is easy to get rid of. Wells, 17 years before the first world dump, wrote about the coming wars, which were all the more dangerous the more terrifying the sadomasochistic mania to invent more and more weapons, using even the most peaceful inventions to their detriment, about the place of the intelligentsia in military cataclysms, about the defenselessness of man against natural forces – whether it be a flood, a meteorite, fascism or an attack by Martians. The book contains clear allusions to historical cyclicality, a harsh criticism of British colonialism, and philosophical insights into the dangers of the technological revolution, whose one-sided discoveries can lead to tragedy, collected from different historical eras and reconstructed in a socio-political perspective.

And even if one reads without reading, the effect of Wells’ prophetic novel on popular culture was truly revolutionary. After all, it was he who discovered aliens for a worldwide audience, setting in motion the flywheel on which almost all of space fiction now swings.

And, returning to good books in movies, I say that every era has its own reading of Welles’ immortal masterpiece, which, like every brilliant book – in any genre – does not get old. In every era, every filmmaker who makes ‘War of the Worlds’ perceives it without a break from his time. In 2005 Spielberg made a movie based on the novel in which the central themes were the defenselessness of man in the face of an external enemy (read: terrorists) and the attempt of the common man not to win the war but simply to get his feet away from the war and save his family.

In the 90’s, ‘Independence Day’ became a symbol of the epic victories of the American people who had just won the arms race, the ‘Cold War’ and the fight for their native capitalist system – along with a plea to trust their president. And the alliance between the military and the government became the hero.

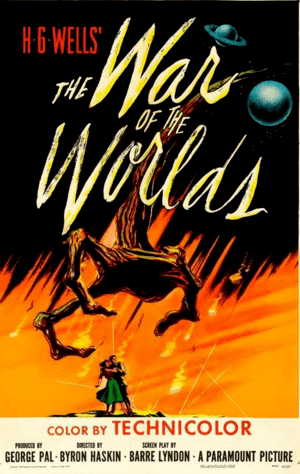

In 1953 Byron Haskin was making ‘War of the Worlds’ about something else entirely. No matter how hard the artists tried to camouflage it, any thinking person would see in this classic film a fiery appeal: “God bless America – don’t let the red plague into our land! And if it does, it will rot away on its own if we are all on our guard!

It’s not hard to understand, given the environment in which ‘The War of the Worlds’ was filmed and by whom. The ‘witch-hunt’ and the obscurantism of McCarthyism had not yet fully subsided, the ‘red menace’ was here, right on the doorstep, the atheists from the USSR were rapidly increasing their influence in the world, and even in America millions were openly or implicitly sympathetic to socialism. Haskin’s ‘The War of the Worlds’ is both a strongly worded warning of a possible war that would be hard to win and at the same time a religious sermon which uses all the clichés of such films, right down to the priest stupidly marching to his death with a cross in his hand and a prayer on his lips, a scene of vulgar stupidity and arrogance which may be second only to that in Mikhalkov’s ‘Burnt by the Sun II’ where the soldier dashes at the tank with a saber. And no less vulgar is the ending, in which yet another religious sermon is given. The pious director Haskin could not do without repeatedly mentioning God, thus contradicting the novel’s concept and Welles’ idea of the ‘self-purification’ of Earth, on which there can be nothing superfluous in principle. Wells was a rigid atheist, and Haskin is a snotty one at the lectern.

The hero changed accordingly. Instead of the scientist-philosopher in the book, here was the scientist-physicist. At that time discoveries in this field interested people much more. In keeping with the times, the hero has a partner with whom he is sure to create a glorious unit of society, especially after the war, puritanical America tried to eradicate the sexual licentiousness that arose in the 30’s. And you’ll find a lot more imprints of the times in this film.

Gene Berry is not bad, but the female lead is immensely annoying. The producers purposely didn’t want to take big stars in the film, but they could well have spared it from the wildly overplayed and unnatural Robinson, whose every appearance spoils the picture.

But 1953’s The War of the Worlds is undeniably a technogenic masterpiece of its time and its own expressive cast. It makes no sense to berate this film – politically it couldn’t have been any different, and it couldn’t have been apolitical either. Besides, it really was a breakthrough that conquered the hearts of the cinematic tribe, and is capable of doing so now.

While technically and morally obsolete, the film nevertheless captures and delights in the amount of work done. It’s not some slapstick movie. It’s everything, the models, the puppets, the makeup, the disappearances, the fires, the destruction of entire cities, the empty cities, the huge crowds, the epic scene in which the madding crowd throws people out of cars, the panic – all this is a huge work, arousing admiration, seeming truly fantastic for the time when all this had to be literally done by hand!!! The filmmakers accomplished a feat, and the film looks fascinating and lively. Isn’t that the highest praise for a 50 year old film, whose genre usually lasts 5-7 years.

And, of course, parallels can be drawn. Whether with history – or with cinema. What has changed? Isn’t this how the military now reacts to displays of hostility? Won’t the mobs behave in the same way? Wouldn’t an attack from the outside be as swift and as helpless before it as they were in 1914, 1939 or 2001? If War of the Worlds is made into a movie in 2020, it will be different and very much the same again. The main theme will change, the atmosphere surrounding the cinema will be different, but what the brilliant Briton said 115 years ago will always be relevant.

It is almost impossible to frighten a modern audience with a classic horror film. But the keenest interest, which this museum piece still arouses, says that badly or well, the creators of this ambiguous film have achieved their aim. Well, it makes no sense to talk about the impact this film had on the sci-fi genre. It can be felt in every third genre film.

P.S. I wonder how the sci-fi artist himself would have reacted to this film. If the producers had hurried up, they could have had time before Welles died – because the script has been hanging around studios since 25. The opinion of the godless and visionary author would be especially valuable today.

Info Blu-ray

Video

Codec: HEVC / H.265 (79.0 Mb/s)

Resolution: Native 4K (2160p)

HDR: Dolby Vision, HDR10

Aspect ratio: 1.37:1

Original aspect ratio: 1.37:1

Audio

English: DTS-HD Master Audio 5.1 (48kHz, 24-bit)

English: Dolby Digital 5.1

English: Dolby Digital 2.0

German: Dolby Digital 2.0 Mono

French: Dolby Digital 2.0 Mono

Subtitles

English, English SDH, French, German, Italian, Japanese, Spanish, Dutch.